The NSW Government has delivered the 2023-24 State Budget in the midst of an affordable housing shortage and a cost-of-living crisis, both of which are having devastating impacts for many households and communities across NSW. This is occurring against a backdrop of widening inequality, with poverty and disadvantage increasingly concentrated, and worsening, in some suburbs and locations, while others experience more favourable circumstances. It is the first budget of the new Labor Government, framed as one that would “fix the fundamentals about what’s wrong with our essential services”.

While NCOSS acknowledges the financial constraints and budgetary pressures faced, and the inclusion of some welcome initiatives that target disadvantaged households, this Budget does not do enough to help those barely hanging on. Nor does it sufficiently address the compounding, structural layers of disadvantage that affect some groups more than others, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, people with disability and multicultural communities.

We are seeing the impacts of the pandemic, inflation and successive disasters continue to play out, particularly on those living in poverty. As more people move into housing stress and struggle to afford a safe, secure roof over their heads, more are going without essentials, using up what meagre savings they had, and taking other drastic measures in order to get by. These are the households in need of urgent assistance, but for whom the Budget has largely not delivered.

The rhetoric around the Budget emphasised a focus on housing affordability, yet there are few investments or measures that will have a significant impact for those doing it toughest. The Essential Housing Package has some welcome investments aimed at priority housing and homelessness, but they are modest at best. This Budget continues the decades of neglect of social housing.

Another core element of the Budget message was responding to the cost of living. We welcome the $100m increase to energy rebates, as well as others such as toll relief and pre-school fee relief. However, these will not do enough for those barely hanging on – living in fear of a rent increase, struggling to care for their family, unable to afford healthcare or experiencing a constant state of anxiety and distress.

And the Budget is almost entirely silent on the challenges facing the social service sector. It invests billions of dollars in vital physical infrastructure, but few measures are directed at bolstering the social infrastructure keeping struggling households from going under. While the Government’s swiftness in confirming annual indexation of 5.75% for many community organisations has been welcomed, this has not necessarily been uniformly applied and it does not help organisations respond to rising demand for assistance and support. This lack of additional investment in these essential services means that people will not receive the timely support or early intervention they need, increasing the likelihood that their circumstances will escalate to crisis, at significant cost to the community and the Government.

We know that poverty is solvable; we just need Governments to act. Our hope is that this Budget is just the starting point for significant and urgent action to come, and that the response from the sector demonstrates how much more is required. NCOSS will continue to push hard for priority action to address the key challenges, both in the months ahead and in the next Budget.

Read our analysis on specific policy areas below:

Housing and Homelessness

Challenge

NSW is in the midst of a housing affordability crisis. It has been decades in the making, and it requires a long-term plan as well as urgent support for those hardest hit.

Those in poverty and on low incomes are bearing the brunt of spiralling housing costs, and it is getting worse. Almost 70% of these households are in housing stress, increasing by 15% since 2022. Worse still, three in ten are paying more than half of their income on rent – this measure of extreme housing stress increased by a substantial 32% since 2022. The impact is particularly acute for private renters and those living below the poverty line, with many likely to rent for their entire lives.

There are more than 56,000 people waiting for social housing with wait times of up to 10 years and more. There is, currently, an estimated shortfall of 221,500 social housing dwellings [1], and a growing shortfall in social housing for Aboriginal households of over 10,000 dwellings [2]. 35,000 people are homeless, nearly a quarter of whom are young people aged 12 to 24 [3]. It is estimated that nearly 5,000 women and children escaping DV are returning to violence or becoming homeless because they have nowhere to live [4].

What’s In the 2023-2024 Budget?

$2.2 billion Housing and Infrastructure Plan

- $300.0 million in reinvested dividends to enable Landcom to deliver an additional 1,409 affordable homes and 3,288 market homes to 2039-40.

- $400.0 million reserved in Restart NSW for the new Housing Infrastructure Fund, to deliver infrastructure that will unlock housing across the State ($100m for Regional).

- $1.5 billion for housing related infrastructure through the Housing and Productivity Contribution.

$224 million Essential Housing Package

- $70.0 million interest-free debt financing for NSW Land and Housing Corporation (LAHC) to accelerate the delivery of social, affordable and private homes primarily in regional New South Wales by funding initial land and site works.

- $35.3 million for housing services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and families through Services Our Way.

- $35.0 million to support critical maintenance for social housing.

- $20.0 million reserved in Restart NSW for dedicated mental health housing.

- $15 million towards a NSW Housing Fund for priority housing and homelessness measures.

- $11.3 million urgent funding to continue the Together Home program in 2023-24.

- $11 million emergency funding for Temporary Accommodation in 2023-24 to support vulnerable people.

- $10.5 million additional funding to the Community Housing Leasing program.

- $10.0 million for a Modular Housing Trial to deliver faster quality social housing.

- $5.9 million urgent funding to Specialist Homelessness Services to respond to increasing demand.

Shared Equity Home Buyer Helper

- $13.0 million expansion for DFV victim-survivors.

Rental reform

- The appointment of a state-first NSW Rental Commissioner.

- Implementing reforms in the rental market:

- a Portable Rental Bonds Scheme

- protecting renters from unfair evictions by legislating reasonable grounds for ending a lease

- making it easier for renters to have pets in homes.

Build to Rent trials

- $60m in the South Coast and Northern Rivers for 100 dwellings, 20 of which will be affordable.

$38.7 million Faster Planning Program

- $24.0 million to establish a NSW Building Commission to support high quality housing and protect home buyers from sub-standard buildings including an additional $1 million in funding for renters’ advocacy organisations.

- $9.1 million to assess housing supply opportunities across government-owned sites, including for the delivery of new social housing.

- $5.6 million for an artificial intelligence pilot to deliver planning system efficiencies.

- Overhauling and simplifying the planning system by redirecting resources from the Greater Cities Commission and Western Parkland City Authority.

Social Housing Accelerator program

- The Government will permanently expand the number of social housing dwellings by around 1,500 through the $610 million Commonwealth Social Housing Accelerator program.

- $79.3m of this has been allocated for Aboriginal Housing.

What does it mean for those doing it tough?

While the budget was premised on laying the foundations for future improvements in housing, it lacks meaningful measures to address the housing crisis, particularly for those most at risk of being forced into homelessness.

With little assistance provided for renters, no significant new investment in social housing, no reforms to improve access to the housing market for people with disability, and inadequate funding increases for overstretched homelessness and tenancy advice services, the Budget provides little relief for low-income and disadvantaged households struggling to keep, or find, a safe and secure roof over their head.

The investments in priority housing, homelessness measures, and temporary accommodation, while very modest, are welcome. We also note the $9.1m allocation to assess housing supply opportunities across government-owned sites and look forward to future investment in social housing identified through that process.

The $35m investment in effective Aboriginal tenancy and housing programs is welcomed, but there is no allocation[5] for urgently needed increased supply of Aboriginal housing.

Repositioning Landcom as a vehicle for re-investment and delivery of affordable housing is positive, but we note that the current commitment will deliver just over 80 affordable homes per year over the next 17 years; this will do almost nothing to address the current estimated shortfall of nearly 80,000 affordable homes for low-income households [6].

What is needed?

We need urgent action and substantial long-term investment to build social and affordable housing, at scale, throughout NSW. The majority of housing-related announcements in the budget are either too small to make a meaningful impact, rely on the private market to boost supply and/or relate to physical infrastructure to support housing, rather than building housing itself. With opportunities through the development of the upcoming National Housing and Homelessness Plan, the establishment of the Housing Australia Future Fund, the Social Housing Accelerator and the Housing Energy Upgrades Fund, as well as an increasing appetite for rental reform across the country, now is the time for real change and a bold new approach.

We hope to see real change in next year’s budget, including a plan to achieve 10% of all dwellings as social and affordable housing by 2041, ongoing funding for the Together Home program, and significant funding boosts for Specialist Homelessness Services and Tenancy Advice and Advocacy Services. The government must also mandate minimum accessibility standards (Silver Level Livable Design) in NSW building regulation, and increase funding of Aboriginal housing from the Social Housing Accelerator Fund to at least $91m to ensure that the funding matches the need.

For renters, we acknowledge positive steps taken by the NSW Government such as establishing the role of Rental Commissioner, a commitment to ending no-grounds evictions, and legislating a portable bonds scheme. However, we need to see more comprehensive reform given the growing numbers of people who rent and rent for longer, and the higher levels of housing stress for this tenure type. Necessary reforms include limiting excessive rent increases, introducing energy efficiency standards, and banning rent bidding.

Cost of Living

The Challenge

The compounding effects of COVID-19, sky-high inflation and successive disasters have had severe impacts on the cost of living in NSW. Interest rate rises and surging rental prices over the last 12 months have substantially reduced housing affordability, reducing the ability of low-income households to pay for other essentials.

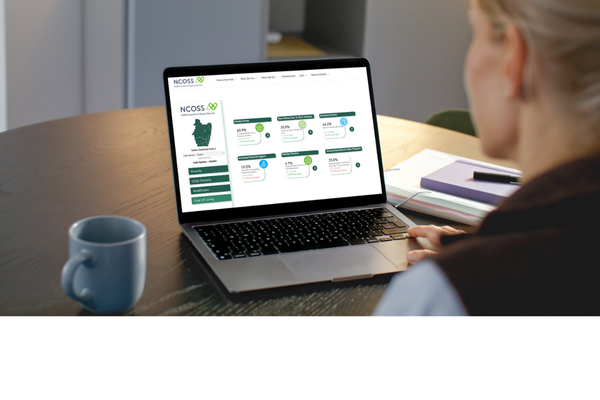

The annual NCOSS Cost of Living in NSW survey for 2023 showed that more low-income households are under increased pressure and told the story of chronic anxiety and stress. 69% are in housing stress and a third of respondents reported they had not been able to pay their utility bills on time, a substantial increase of 38% since 2022.

More people are taking ‘last resort’ measures to get by, such as skipping meals, not undertaking essential travel and going without prescribed medication and health care. More are becoming reliant on Buy Now Pay Later, borrowing from friends and families, and draining their savings. Concerningly, the survey highlighted low levels of awareness and uptake of many cost-of-living rebates.

What’s In the 2023-2024 Budget?

Energy (From 1 July 2024)

- Low Income Household Rebate and Medical Energy Rebate will increase from $285 to $350.

- Family Energy Rebate will increase from $180 to $250 for those receiving the full rate. For those on a partial rate (who also receive the Low Income Household Rebate) the assistance will move from $20 to $30.

- Seniors Energy Rebate will increase from $200 to $250.

- The Life Support Rebate will increase for each piece of equipment by 22%.

Transport

- $60 weekly toll cap for private motorists from 1 January 2024. The program will run for 2 years and is in addition to the Toll Rebate Scheme.

- From Monday 16 October, cheaper weekend fares will be expanded to include Fridays, meaning people will receive a 30% fare discount on Metro, train, bus and light rail services.

Rebates for Kids

- Extending the Active Kids and Creative Kids Voucher Programs to 31 January 2024, and then transitioning to a combined “Active and Creative Kids NSW” voucher program that will be means tested. The cost of this measure is $159.3 million over four years to 2026-27.

- First Lap Learn to Swim Active Pre-Schooler Voucher has been reduced to $50 per child aged between 3 and 6 years not yet enrolled in school to attend swimming lessons.

What does it mean for those doing it tough?

Many households will be paying more for energy considering recent price increases and the likelihood that NSW will be experiencing high temperatures this summer. In this context, an increase to energy rebates will provide much needed and welcomed assistance for low-income households. But we know from take-up rates and feedback from frontline community organisations, that the complexity of application processes can be a barrier for vulnerable community members struggling with language, literacy, technology or other issues.

The Active Kids, Creative Kids and First Lap vouchers are some of the most accessed rebates that the NSW Government offers. These will now be means-tested and reduced in value. While this more targeted approach retains access for lower income households, the reduced value may limit the ability of these families to participate in eligible activities.

Many of Greater Sydney’s existing toll roads are found in and around areas with higher concentrations of disadvantage, particularly in Western and South-West Sydney (e.g. M4, M5 and M7). This increases the likelihood that people living on low incomes will have to utilise toll roads to access employment, social connections, and other amenities.

The toll cap will reduce budget pressures on these households and increase their ability to engage in essential travel using private vehicles. But it does not help those who are dependent on public transport to meet their mobility needs. It is positive that there will be no change to the weekly travel cap of $25 for Opal concession fares on public transport, but concession fares before this point will rise, along with other fares, by an average of 3.7%. This is less than inflation, but is still an additional cost pressure for people living below the poverty line, including those in receipt of JobSeeker or Youth Allowance.

What is needed?

Energy rebates and costs

NCOSS appreciates that the NSW Government has increased a few cost-of-living rebates, targeting vulnerable households to deliver much needed, additional relief. It is a positive start, but more needs to be done to increase awareness, address equity issues, and ensure that relief reaches those in those in greatest need.

Fixed-rate energy concessions do not deliver equity between households with different energy needs, whether this arises because of household size, housing condition or unique needs. Percentage-based energy rebates would better support equity and could be designed in a way that is budget neutral.

Consideration also needs to be given to ensuring that online and in-person application processes and eligibility requirements for cost-of-living rebates are streamlined, making them easy to navigate and straightforward for everyone to complete.

Further, there is a need to address the significant gaps in awareness of cost-of-living rebates, through targeted awareness campaigns. This should include partnering with local neighbourhood and community centres to ensure that the most vulnerable community members are able to receive advice, support and assistance in a safe and welcoming environment. Before the next budget, the Government must also look to reforms that prevent disproportionate energy costs for those doing it toughest, including improving the energy efficiency of homes (particularly for renters), and supporting electrification for low-income households.

Public transport

Expanding public transport concessions to Commonwealth Health Care Card holders would help ensure that more low-income households struggling with rising transport costs can benefit from subsidised travel. This, in turn, would support them to participate in their communities and more actively engage in education, employment and other opportunities.

Similarly, extending the $2.50 per day Opal fare that is available to seniors and pensioners, to others on income support payments would ensure more affordable travel for those struggling below the poverty line.

Food security

Finally, the Government should turn its mind to addressing food security. Community organisations report significant, ongoing demand for assistance from food pantries, community kitchens and distribution centres across the state, despite additional COVID-related funding for this purpose coming to an end. They highlight that the existing system is complex and straining under rising demand, hampered by lack of clarity regarding roles and responsibilities and insufficient coordination at the local level.

Releasing the Review of Food Relief Provision commissioned by the former state government in 2021; and establishing a taskforce of NGO experts to advise on system improvements would be valuable starting points.

Disasters and Building Resilience

The Challenge

The frequency, duration and severity of extreme weather events and disasters is increasing, straining individuals, communities and government agencies. Disadvantaged households and communities are the most impacted and least able to prepare, respond and recover.

The lasting impacts of the 2022 floods, following on from COVID-19 and the Black Summer fires, have again highlighted the essential role of place-based social service organisations when emergencies and natural disasters occur. During and after these disasters, local non-government organisations (NGOs) have been at the forefront of the response and recovery, supporting shattered communities to heal and rebuild.

Extended time in temporary or unsuitable living arrangements, uncertainty about government programs, the compounding impacts of multiple emergencies and the sheer scale of the impacts, have meant ongoing trauma and continued demand for the assistance of local services. However, disaster funding has been one-off, short term, and crisis-driven, leaving communities to fend for themselves after the media spotlight has moved on. Given lack of growth funding in the face of rising demand, local NGOs do not have the resources to meet the ongoing needs of disaster-impacted communities.

Local NGOs are insufficiently recognised as a core part of NSW’s emergency management system, resulting in fractured and inadequate responses to disasters and exacerbated impacts on the most vulnerable.

What’s In the 2023-2024 Budget?

Natural disaster support and response programs

- $3.2 billion for disaster relief and recovery programs, which is eligible for co-contribution from the Australian Government under the Disaster Recovery Funding Arrangements

- $299.3 million for Transport for NSW to restore roads damaged by disasters

- $150 million for the NSW Land and Housing Corporation to deliver replacement, substitute and new social housing in flood impacted locations

- $128.3 million to repair critical water and sewage infrastructure damaged in flood events

- $99.9 million for the state-funded Resilient Lands Program

- $96.0 million for NSW Land and Housing Corporation to deliver social housing across flood impacted locations in Northern New South Wales

- $58.0 million for Flood Recovery Support for the Department of Customer Service, including the Back Home Program

- $5 million to Resilient Lismore and the Reece Foundation to support the Two Rooms Project to help flood survivors get back into their homes following the 2022 floods in Lismore

- $3.3 million to invest in a natural disaster detection system to better protect communities in high-risk areas

NSW Reconstruction Authority

- $115 million to increase funding for the NSW Reconstruction Authority

What does it mean for those doing it tough?

The measures in this Budget demonstrate that the Government appreciates the importance of responding to disasters and building resilience, but they fall short of what is required and miss the vital role played by the NGO sector.

Repairing and improving road networks impacted by disasters will make a difference to the recovery of local communities, and contribute to their readiness for future disasters. Similarly, repairing other physical infrastructure such as water and sewerage is a critical role of Government. However, there is little in the Budget that will address the long term impacts and ongoing trauma experienced by communities. Funding for the NGO Flood Support Program in the Northern Rivers region was not continued in this Budget, despite multiple organisations raising the alarm that the removal of critical supports at this point risks undermining the recovery of traumatised and displaced community members. It is another example of stop-start funding harming recovery efforts that are already under immense pressure.

What is needed?

The Government must ensure that it takes a considered and whole-of-community approach to disasters and resilience, and broaden its focus beyond physical infrastructure. The investments in this Budget are a good start, but more is required. This includes:

- Providing additional investment in NGOs working in communities impacted by recent disasters, so that they can continue their support of those hardest hit and to reduce long-term social and trauma impacts.

- Recognising that local NGOs are at the heart of their communities and play a critical role in managing the human impacts of disaster. As well as being at the frontline of response and recovery, they can help build resilience and preparedness to mitigate the impacts , particularly among those most vulnerable. This requires enhanced core funding, and strengthening NSW’s overall disaster capability by leveraging existing social service infrastructure.

- Directing some of the increased funding for the NSW Reconstruction Authority to the NGO sector to build resilience, awareness and preparedness, particularly among those at most risk. This should include pilot funding for ‘backbone’ organisations to coordinate across the NGO sector, build capability and local planning, and connecting to emergency management systems and agencies.

Child Wellbeing and Development

The Challenge

NCOSS’ recent Mapping Economic Disadvantage in NSW report highlights that children still have the highest rate of poverty of any age bracket at 15.2%, despite a reduction since 2016. Disturbingly, childhood poverty is becoming increasingly concentrated in Western and South-Western Sydney, with areas such as Guildford and South Granville reaching rates of over 40%.

Against this backdrop of widening inequality, children in NSW have faced major upheavals and disruptions through COVID-19, climate disasters, and increasing financial stress on families due to the cost-of-living crisis. NCOSS’ Cost of Living in NSW 2023 survey showed the intense mental health impacts of the crisis and the impact it is having on families with kids, particularly single parents, 90% of whom reported going without essentials or being unable to pay for them.

Analysis by Impact Economics and Policy also showed that, as a result of the upheavals of the past few years, there has been a 13.4% increase in kids starting school developmentally vulnerable; an additional 13,401 children at risk of significant harm between 2018/19 and 20/21; and 220,000 students who missed on an average 15 weeks of schooling due to lockdowns and who risk substantial lifetime earning losses as a result.

The child protection and out-of-home care system continues to fail to deliver for vulnerable Aboriginal children, who are eleven times more likely to be in out-of-home-care (OOHC) compared to non-Aboriginal children. While the Family is Culture Review identified a clear roadmap to address the overrepresentation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in care, to date there has been a lack of meaningful, genuine engagement and partnership with the Aboriginal community on progressing the Report’s recommendations. Where progress has been made, these can be described as piecemeal at best.

What’s In the 2023-2024 Budget?

Education and Care

- $682.7 million additional investment in four new primary schools and 10 new high schools across NSW

- Permanent, targeted literacy and numeracy tutoring programs in primary and secondary schools in a $278.4 million program over four years to 2026-27.

- $849 million investment in new Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) services, which includes:

- Fast-tracking $769.3 million for 100 new preschools on public school sites

- $60 million towards new and upgraded non-government preschools to increase affordable, high-quality preschool in the areas of most need.

- Up to $20 million to support the growth of not-for-profit ECEC services in high demand areas.

- $1.6 billion of preschool fee relief from an expanded affordable preschool program, including:

- Providing $500 per year in fee relief for children attending 3 year old kindergarten in long day care

- Providing $4,220 per year in fee relief for 3 to 5 year olds in community and mobile preschool

- Providing $2,110 in fee relief for children aged 4 years and older attending preschool in long day care.

- 250 additional school counsellors to support students with mental health needs and disabilities

- $8 million to double the School Breakfast 4 Health program to 1,000 schools.

Out of Home Care and Permanency Support

- $200 million (in 2023-24) in additional funding for the Department of Communities and Justice to deliver the Out of Home Care and Permanency support program. The funding ensures continuation of services while the Government reviews funding models over the longer term. The majority of this will go towards NGO service providers and the provision of emergency arrangements for children and young people who cannot live safely at home.

What does it mean for those doing it tough?

Universal, high-quality early learning has the potential to deliver life-changing impacts for children in NSW, particularly those experiencing disadvantage. ECEC provides an environment where children can thrive socially, emotionally and developmentally, and prepare for the transition to school.

Fast tracking the building of preschools in areas with most need has the potential to give more children access to vital development opportunities, while fee support will give some help to families struggling to balance the household budget. Similarly, the building of new public schools, particularly in Regional NSW and Western and South Western Sydney, will deliver critical physical infrastructure that is the starting point for educational engagement and attainment.

While the $200 million to deliver the Out of Home Care and Permanency support program is necessary to support children and young people in care, it continues the focus at the crisis end of the service system without any further investment in early intervention.

What is needed?

Children and families, particularly those experiencing disadvantage, need the right supports at the right time, so that day-to-day challenges don’t escalate to crises. The Government needs to outline a clear plan for supporting children and families most at risk, including substantial investment in evidence-based early intervention that breaks the cycle of disadvantage and support families to stay together.

Struggling families can be at a loss when it comes to navigating our complex, fragmented service systems, and fail to receive the assistance they require. Too often, cost-of-living pressures build to crisis point, pushing families into emergency departments, the justice system, child protection services and homeless shelters. Investing in the expansion of models like the NCOSS ‘School Gateway project’ would make it easier to connect with support at the right time and avert crises.. This place-based, whole-of-family approach uses the familiar environment of the school, in at-risk communities, as the gateway to health and wellbeing services, emergency support, improved educational outcomes, and social connection.

Aboriginal children, families and communities have the right to live in thriving communities, connected to culture and Country. We need the Government to take a holistic view of the Family is Culture Review and take urgent action on the Report’s recommendations by advancing the identified five community-led priority areas for implementation:

- Strengthening system accountability and oversight – including establishing an independent commission with an Aboriginal Commissioner and an Aboriginal Advisory Body appointed in consultation with the Aboriginal community;

- Expediting the suite of legislative reforms to strengthen safeguards for Aboriginal children and young people and their families;

- Significantly greater investment in early support and keeping families together – at least equal to the proportion of Aboriginal children in the child protection system and directed through an Aboriginal commissioning framework;

- Embedding the Aboriginal Case Management Policy and Practice Guidance – including the establishment of Aboriginal Community Controlled Mechanisms, Community Facilitators and Aboriginal Family Led Decision-Making;

- Embedding Indigenous data sovereignty – establishing the systems, structures and processes to enable communities to collect, own and use their data.

Sector Sustainability

The Challenge

The social service sector is the largest employer in Australia and is projected to grow even further, contributing $15.4 billion each year to the NSW economy. However, the sector is facing significant sustainability challenges.

Frontline services increasingly report that they cannot keep up with demand, as the needs of the community are becoming more complex and widespread due to the impacts of COVID-19, natural disasters, the affordable housing shortage and cost of living challenges.

Many – such as neighbourhood centres and services providing domestic and family violence, homelessness, tenancy advice, financial counselling, mental health, and child and family supports – report that they are seeing more people who have not previously needed help before, and more who are in crisis. They also report an increase in those reaching out who are in the workforce, but struggling to get by.

In this context, long-standing challenges associated with lack of growth funding, over-reliance on short-term funding boosts, and uncertain and inconsistent approaches to annual indexation are becoming more acute. They are contributing to workforce shortages, health and safety issues and service viability concerns.

What’s In the 2023-2024 Budget?

- $34.3 million to support 20 Women’s Health Centres providing health and mental health services for women.

- $8.1 million to Redfern Legal Centre to expand their financial abuse service statewide.

- $4.4 million over three years to establish a new specialist multicultural domestic and family violence centre in southwest Sydney.

- $1 million for renters’ advocacy organisations.

- A taskforce will be established to deliver more job security and funding certainty for the NSW community services sector.

- Increased grant payments to non-government organisations, indexed at 5.75% for 2023-24.

What does it mean for those doing it tough?

While the modest additional investments for social services announced in the budget are welcome and will benefit some, they are piecemeal and insufficient in light of the challenges faced.

Women from low socio-economic backgrounds, priority populations and those who are most at-risk will benefit from the additional funding for Women’s Health Centres, which will enable them to continue operating to provide women with a safe, private and women-focused space to address mental and physical health concerns. The new specialist multicultural domestic and family violence centre will provide vital supports in Sydney’s growing South West, where the impacts of economic disadvantage are most acutely felt.

Similarly, the state-wide expansion of Redfern Legal Centre’s financial abuse service will enable more people across the state to access information and support to protect themselves and recover from financial abuse. Renter’s advocacy organisations will have some increased capacity to advocate, educate and advise in relation to renters’ rights.

For the sector more broadly, indexation of 5.75% to eligible organisations is a higher rate than that awarded in other states and territories, and signals awareness of the challenges faced. However, there remains a need for a consistent, transparent and evidence-based approach to annual indexation and for population-based funding models that better respond to rising demand.

What is needed?

The Budget’s strong focus on better recognising and supporting the public sector’s delivery of essential services is welcomed. But the equally critical role of the non government social service sector in providing essential services for those most in need must also be better recognised and supported.

Similarly, while investment in essential physical infrastructure such as public schools and hospitals for under-serviced growth areas is much needed, so too is investment in social infrastructure – services that support those doing it toughest to get their lives back on track and participate in their communities.

Collaborating with the sector to develop an evidence-based, consistent approach to indexation to reflect the real cost of service provision is long overdue; as is the development of a population-based approach to funding social services aligned with growth, changing demographics and demand.

In the meantime, the provision of core funding to neighbourhood centres and other similar place-based services – which act as hubs for accessing support, social connection and pathways to other assistance – would be a welcome development and bring NSW more in line with neighbouring jurisdictions. Bolstering, on a recurrent basis, the capacity of essential programs facing rising demand from the cost-of-living crisis, including tenancy advice, mental health supports, and financial counselling, would also make a significant difference.

Budget Responses from the Sector

- NCOSS Media Release

- CHIANSW Media Release

- Homelessness NSW Media Release

Sector Priorities

- NCOSS: Barely Hanging On – The Cost of Living Crisis in NSW 2023

- ShelterNSW Pre Budget Submission

- CHIANSW State Budget 2023 Priorities

- Homelessness NSW Pre Budget Submission

[1] Van Den Nouwelant R, Troy L, Soundararaj B 2022 Quantifying Australia’s unmet housing need: A national snapshot viewed 19 June 2023 https://cityfutures.ada.unsw.edu.au/documents/699/CHIA-housing-need-national-snapshot-v1.0.pdf

[2] Brackertz N Davison J Wilkinson A 2017 How can Aboriginal housing in NSW and the Aboriginal Housing Office provide the best opportunity for Aboriginal people? Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute viewed 26 July 2023 https://www.ahuri.edu.au/sites/default/files/migration/documents/AHURI-Report-October-2017.pdf

[3] Viewed 19 June 2023 https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/housing/estimating-homelessness-census/latest-release

[4] Equity Economics 2021, Rebuilding Women’s Economic Security – Investing in Social Housing in New South Wales, Sydney

[5] Apart from an allocation from the federally funded Social Housing Accelerator

[6] Van Den Nouwelant R, Troy L, Soundararaj B 2022 Quantifying Australia’s unmet housing need: A national snapshot viewed 19 June 2023 https://cityfutures.ada.unsw.edu.au/documents/699/CHIA-housing-need-national-snapshot-v1.0.pdf